The position of the North Pole shifts gradually throughout time. The axis of the Earth has a tiny wobble, and since the pole meets with the axis, it too wobbles. Scientists estimate that the pole wobbles around 30 feet every seven years. Instantaneous pole refers to the precise point of the pole at any given time.

Scientists have observed in recent years that the axis is fast shifting eastward due to climate change. According to Surendra Adhikari, an Earth scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, the north pole has moved around 75 degrees to the east since the year 2000, in the direction of the Prime Meridian, which passes through Greenwich, England.

In a 2016 National Geographic story, Adhikari stated that the axis had changed around 10 centimeters (4 inches) every year. Scientists assume that the fast melting of ice sheets has created a mass shift. According to a 2005 Live Science article, melting ice shifts mass by providing water to the seas and easing the weight on ice-covered terrain.

Who discovered the North Pole?

The first adventurer to approach the North Pole is really the subject of some debate. Robert Peary claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1909, but he lacked sufficient evidence, and many have maintained that he did not. The first confirmed visit to the North Pole was made in 1926 by explorers Roald Amundsen and Umberto Nobile, who sailed over the pole in the Norge airship.

How to get to the North Pole

Although inaccessible for the majority of the year, the North Pole is accessible in June and July, when the ice is thinner, or in April if traveling by helicopter. All trips to the North Pole begin and conclude in Helsinki, Finland, where you’ll board a chartered flight to Murmansk, in Northwest Russia, to board your ship.

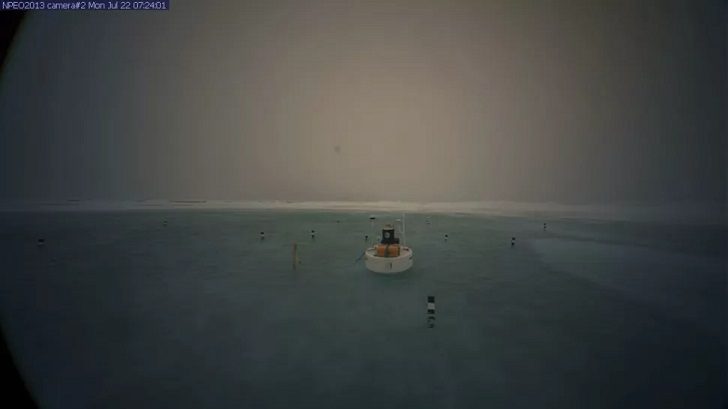

From Murmansk, icebreaker ships are the most popular mode of transportation for guests. Crush through multiyear ice to reach 90 degrees north, where you may unload, stand above 13,000 feet of Arctic seas, and observe an ice sheet mosaic.

Canada, Russia and Denmark are each attempting a North Pole land grab

According to recent news reports, the governments of Canada and Russia are fighting for control of the territory, much like when most of Africa was divided among colonial powers. Canada and Russia’s efforts to identify their rights to the soil and subsoil of the North Pole are, however, part of a well-established international procedure.

According to the rules of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), both governments have the right to resources such as oil, gas, minerals, and anything else that occurs on the ocean floor more than 200 nautical miles from their respective coastlines. States have the authority to determine whether or not they possess an extended continental shelf, which is a natural extension of the undersea landmass.

They must perform exhaustive measurements (not an easy undertaking in the Arctic) and then submit their findings to a UNCLOS-established body for scientific review. This United Nations body assesses simply if the science provided is accurate. The states concerned are then responsible for resolving any overlaps. Russia, Canada, and Denmark are following the regulations; thus, there is no reason to anticipate a dispute.