Timekeeping sounds simple until you try to measure it perfectly. Physicists have chased better clocks for decades, each generation shaving off tiny errors that still matter a lot. GPS, financial networks, power grids, and space missions all rely on clocks that refuse to drift. Even a billionth of a second can cause real problems.

Now, a UCLA-led physics team has cleared a major obstacle that slowed progress for years. They did it by borrowing a method that jewellers have used for centuries. The result is a cleaner, cheaper, and far tougher path toward nuclear clocks, devices that could outperform every clock on Earth.

This breakthrough does not come from exotic materials or massive machines. It comes from steel, electricity, and a fresh look at old assumptions. Sometimes progress shows up in plain sight.

How Physicists Turn Jewelry Science Into Clock Science

These crystals were fragile, difficult to grow, and slow to make. Each attempt took years of work and used at least one milligram of rare thorium.

That approach created a serious bottleneck. Thorium-229 is incredibly scarce. Only about 40 grams exist worldwide for research. Burning through milligrams at a time made the process expensive and limited. It also kept nuclear clocks locked inside controlled labs rather than in real devices.

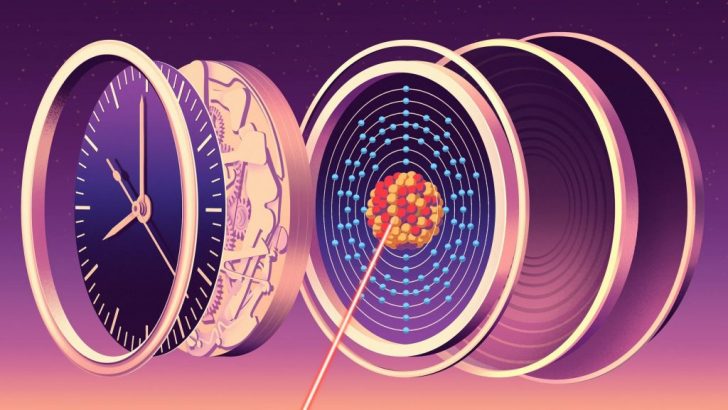

The UCLA team questioned the core assumption behind the crystals. They realized the laser did not need to pass through the material at all. With that insight, the entire design changed.

They turned to electroplating, the same method used to coat rings with gold or silver. Using electricity, they deposited an ultra-thin layer of thorium directly onto stainless steel. This required about 1,000 times less thorium than the crystal method. Instead of a fragile crystal, the result was a solid piece of steel.

Steel changed everything. It is durable, easy to handle, and ready for real-world use. The physics also got simpler. On steel, excited thorium nuclei release electrons rather than light. Detecting electrons means measuring electrical current, one of the easiest signals to track in a lab. Fewer parts. Fewer failures. Faster progress.

Why Nuclear Clocks Are Important

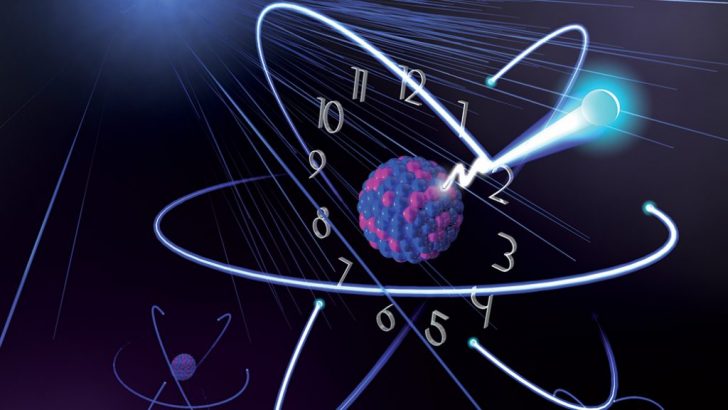

Atomic clocks already sound perfect. Some would not lose a second over the age of the universe. That sounds unbeatable until you look closer. Atomic clocks rely on electrons, which sit far from the nucleus and react to heat, magnetic fields, and other noise.

That makes it naturally stable. Less wobble means better timekeeping.

Thorium-229 is the key. It has a rare nuclear transition that can be triggered by lasers we already know how to build. No other known element offers this feature. That makes thorium-229 the only practical candidate for a nuclear clock today.

Scarcity made efficiency critical. The electroplating method directly solves that problem. Using microscopic amounts of thorium stretches the global supply and opens the door to multiple working clocks instead of a single fragile experiment.

Precision at this level changes how scientists test reality itself. Time becomes a probe, not just a measurement.

One of the biggest drivers behind nuclear clocks is navigation. GPS works only when satellites constantly sync their clocks with ground stations. Lose that connection, and accuracy drops fast. That is a problem for submarines, spacecraft, and remote drones.

A nuclear clock could keep perfect time on its own for months or longer. A spacecraft could navigate deep space without calling home. A submarine could remain submerged without losing position accuracy—that kind of autonomy matters for both exploration and security.